The Rise of Long-Form Generative Art

The most notable exceptions are probably "live" programs that could be infinitely refreshed. These share some of the same concerns. With that said, in these new models, the fact that the artist is targeting a specific output set size, combined with the fact that every output will be put up for collection (with no skipping) makes the intent feel significantly different to me.

There's a new art form on the rise. Generative art has existed since the 1960s, but the new on-chain generative art platforms are pushing the medium in an exciting new direction. While many of the generative techniques are the same, the goals for the program output are wildly different from before. The direct path from the script to the viewer, as well as the large number of iterations, encourages artists to create a special class of artistic algorithm, what I'll refer to here as long-form generativism. In this essay, I'll discuss what makes these algorithms different, and how we can analyze their quality.

Generative Art In The Past

Historically, generative art had some typical qualities that were taken for granted.

First, there was almost always a "curation" step. The artist could generate as many outputs as they pleased and then filter those down to a small set of favorites. Only this curated set of output would be presented to the public.

Second, the size of that final curated set was generally small. In fact, it was extremely common to choose just a single best output to show. At most, perhaps a dozen iterations would be shown.

There have been exceptions [1], but this was the way things were usually done. For an example from my own work, here are three iterations from Lines, a program from 2017. I initially generated about 200 images from the program, and then curated that down to a final set of just 10 images that I felt captured most of the interesting characteristics.

Lines 1A, 2017

Lines 1B, 2017

Lines 1C, 2017

The New World

Today, platforms like Art Blocks (and in the future, I’m sure many others) allow for something different. The artist creates a generative script (e.g. Fidenza) that is written to the Ethereum blockchain, making it permanent, immutable, and verifiable. Next, the artist specifies how many iterations will be available to be minted by the script. A typical choice is in the 500 to 1000 range. When a collector mints an iteration (i.e. they make a purchase), the script is run to generate a new output, and that output is wrapped in an NFT and transferred directly to the collector. Nobody, including the collector, the platform, or the artist, knows precisely what will be generated when the script is run, so the full range of outputs is a surprise to everyone.

Note the two key differences from earlier forms of generative art. First, the script output goes directly into the hands of the collector, with no opportunity for intervention or curation by the artist. Second, the generative algorithms are expected to create roughly 100x more iterations than before. Both of these have massive implications for the artist. They should also have massive implications for how collectors and critics evaluate the quality of a generative art algorithm.

With long-form works, the artist has nowhere to hide, and collectors will get to know the scope of the algorithm almost as well as the artist.

Analyzing Quality

As with any art form, there are a million unpredictable ways to make something good. Without speaking in absolutes, I'll try to describe what I think are useful characteristics for evaluating whether a long-form generative art program is successful or not, and how this differs from previous (short) forms of generative art.

Fundamentally, with long-form, collectors and viewers become much more familiar with the "output space" of the program. In other words, they have a clear idea of exactly what the program is capable of generating, and how likely it is to generate one output versus another. This was not the case with short-form works, where the output space was either very narrow (sometimes singular) or cherry-picked for the best highlights. By withholding most of the program output, the artist could present a particular, limited view of the algorithm. With long-form works, the artist has nowhere to hide, and collectors will get to know the scope of the algorithm almost as well as the artist.

What are the implications of this? It makes the "average" output from the program crucial. In fact, even the worst outputs are arguably important, because they're just as visible. Before, this bad output could be ignored and discarded. The artist only cared about the top 5% of output, because that's what would make it into the final curated set to be presented to the public. The artist might have been happy to design an algorithm that produced 95% garbage and 5% gems.

Six iterations from Archetype, by Kjetil Golid, 2021. This long-form project set an incredibly high bar for consistent quality.

That type of design doesn't work with long-form generative art. Instead, the artist needs to ensure that bad results are extremely rare. The algorithm can't stumble across great results by luck anymore, it needs to produce them dependably. Speaking as an artist, I can assure you that this is difficult. The logic around how generation works must be much more sophisticated. There's also a need for what is essentially a "quality assurance" process. The artist must systematically work through the full high-dimensional space of possible outputs, and ensure that all of them are up to par. For Fidenza, I spent about two months on this step. I repeatedly generated large sets of output, looked for the weakest examples, and figured out ways to improve or eliminate those cases.

The need for consistent minimum output quality is dramatically complicated by the second new demand of long-form generativism: the output space of the algorithm must be varied enough to justify the set of 100, 500, or 1000 iterations generated from it. With a top-class algorithm, every output will have something new about it, a little surprise that teaches you more about what is possible. You shouldn't ever get bored flipping through the results. If you do, edition size should have been smaller, or the algorithm should have expressed more variety.

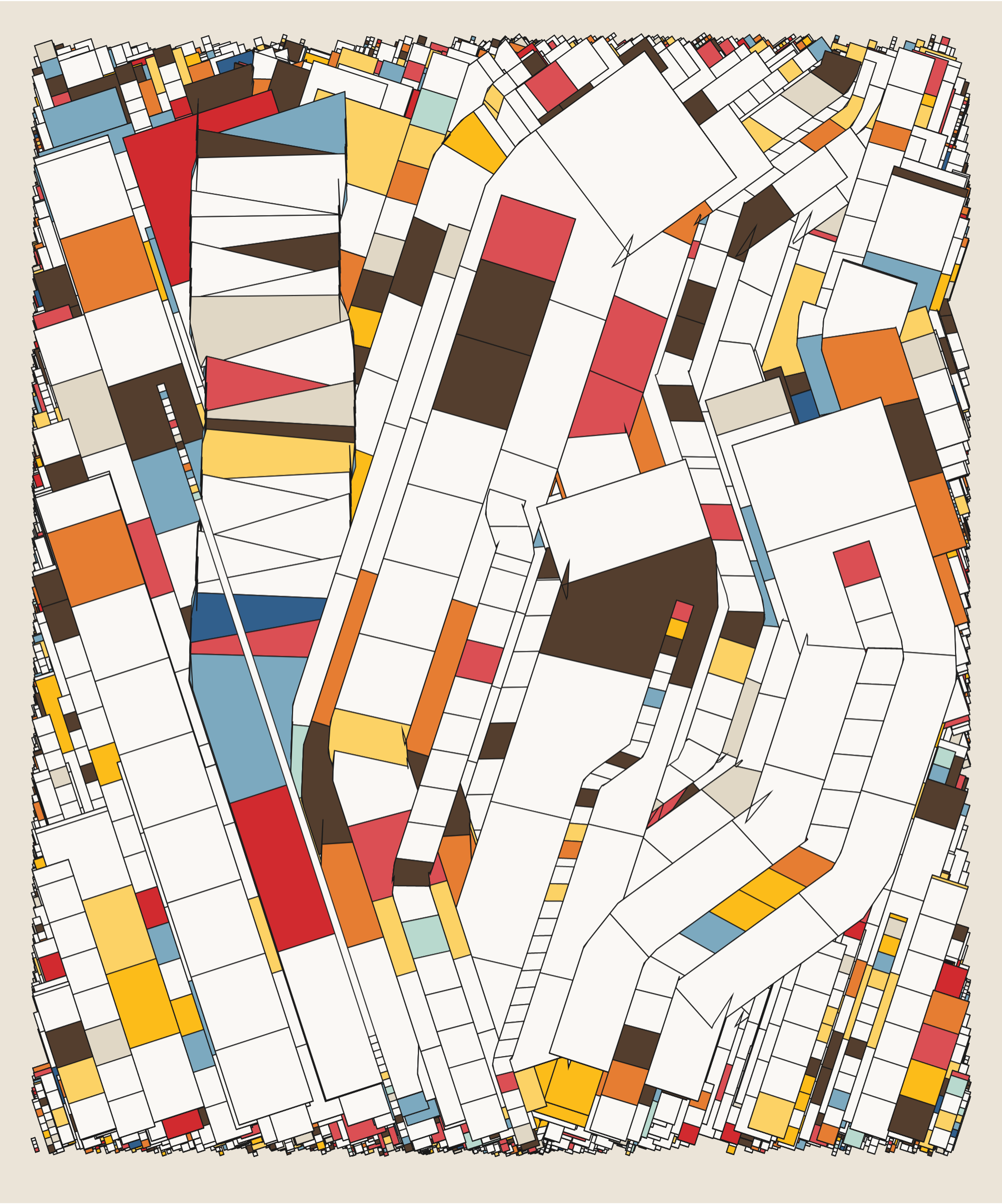

Fidenza #222, 2021

Fidenza #479, 2021

Fidenza #430, 2021

With that said, the artist should be careful about how they add variety to their program. Simply jamming in new elements can make the entire collection less coherent. It's better to carefully craft something that makes sense as a unified whole, something that is the full expression of a single idea. Just as we can judge the success of a long-form generative algorithm by the best, worst, and average outputs, we can also judge it by its "collective unity". It should make sense as a whole, to the extent where the removal of any one component would be harmful.

In summary, long-form generative art introduces the new demands of consistent quality and high variety, while maintaining the existing need for unity across all output from a program. Right now, few artists are capable of navigating this balance, but I have no doubt that will change. The art form is just ramping up, and generative artists are starting to become familiar with the new dynamic. Short-form generative work will continue to exist and will continue to be the best fit for many artistic visions, but right now long-form is the fertile, unexplored space. I look forward to seeing all of the amazing work that will be created over the next few years!

–

From time to time, I write about my thoughts and artistic process. If you'd like to be notified the next time I publish an essay, sign up for my newsletter in the menu.